Ljudsko dostojanstvo i kraj života – 3. dio: Kraj života i pravo

This is a third in the series of three articles titled “Human Dignity and the End of Life”.

[tabs]

[tab title=”English”]

The legal debate concerning the end of life is also characterized by contemporary medical interventions in the lives of the sick and dying, the right to life of those concerned, their fundamental freedoms, the right to respect private and family life and other rights in accordance with national and international laws, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (hereafter: the Declaration), the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (hereafter: the Convention), the European Social Charter, and others.

The foundation of social and political commitment to human equality lies in the firm belief that every human person has dignity which ensures them their rights and respect, because he or she is a human person, regardless of race, gender, appearance, belief, or any other characteristic. The international legal framework protects the right to life of every person, which is the first among the enumerated rights of the Convention, and it poses a demand upon countries to protect the lives of the most vulnerable and weak. It is important to note that international law does not recognize so-called “right to death” nor is it a part of the international legal guidelines. Apart from protecting the most vulnerable individuals, the country also has an interest in protecting the ethical integrity of the medical profession in order to ensure citizens’ trust in that profession.

Systematic protection of patients’ rights in Europe began with the document entitled “Rights of the sick and dying” adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 1976 and amended in 1979 by the Standing Committee of the Hospitals of the European Union with the document “European Charter of Rights for Hospital Patients.” In order to prevent situations in which patients are not given sufficient attention and are not treated in accordance with their dignity, the documents were developed on the basis of the Declaration and the European Social Charter. Contemporary legal debates on the end of life mostly focus on Article 2, which requires that the country should not only abstain from inflicting death but should also protect life, and Article 8 of the Convention, which guarantees the right to respect for private life.

An additional contribution of the Council of Europe to the matter is given through several documents confirming the consensus of European countries that oppose euthanasia and assisted suicide. We highlight two Recommendations and one Resolution adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe:

– Recommendation 779 (1976): “the doctor must make every effort to alleviate suffering, and that he has no right, even in cases which appear to him to be desperate, to intentionally hasten the natural course of death” (§7).

– Recommendation 1418 (1999) affirms that the right to life of the sick and dying must be guaranteed even when they express their desire to die.

– Resolution 1859 (2012): “Euthanasia, in the sense of the intentional killing by act or omission of a dependent human being for his or her alleged benefit, must always be prohibited.”

The mechanism for ensuring implementation of the Convention is the European Court of Human Rights (hereafter: the Court) to which the person who is a victim of a violation of fundamental human rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Convention may apply, according to the Article 34 of the Convention. The Court’s judgment that initiated legal aspect debate regarding the end of life was in the case Pretty v. United Kingdom in 2002 rejecting the appeal of an incurably ill British citizen Diane Pretty and denied the “right to death” by euthanasia.[1] Pretty v. United Kingdom is important for the following two elements:

1) “Article 2 cannot, without a distortion of language, be interpreted as conferring the diametrically opposite right, namely the right to die; nor can it create the right to self-determination in the sense of conferring on an individual the entitlement to choose death rather than life.” (§39)

[…]

“The right to death, whether at the hands of a third person or with the assistance of a public authority, cannot be derived from Article 2 of the Convention.” (§40)

2) “Moreover, the Contracting States enjoy a margin of appreciation in assessing whether and to what extent differences in otherwise similar situations justify a different treatment.” (§ 87)[2]

First and foremost, this judgment made a clear difference between rights and freedoms, and emphasized that from the right to life does not imply or create a so-called “right to death.” While freedoms have a positive (the right to act) and a negative aspect (the right not to act) in the case of protection of life, the Court explicitly states that the right to life has no diametrically opposed right. Secondly, the Court found that the Contracting States, according to the “margin of appreciation” concept, have a certain discretion in decisions concerning the balance between the individual’s rights and the society’s interests.

Article 2 of the Convention states that “No one shall be deliberately deprived of life,” as well as specific exceptions to this right which the Convention prescribes for the protection of general interest or a greater goal. However, these exceptions do not include request nor consent of the interested parties for euthanasia or assisted suicide. Life and the right to life form the basis from which all other rights are derived, and which stands in apparent contradiction to euthanasia.[3] The case Pretty v. United Kingdom affirmed that the right to life “constitutes an inalienable attribute of the human person and that it form[s] the supreme value in the scale of human rights”[4] and protects “any person.”[5]

The concept of human rights implies protection of the human individual from becoming an object of a struggle for power and the interests of a State, and emphasizes that a person in their dignity must always be seen as a goal and never as a means. The intrinsic dignity of a person does not depend on circumstances and no society or State can give or deny it because dignity precedes the State. Human dignity is the basis for the Declaration, and an inspiration to the Convention, which is based on the recognition of inherent dignity to all members of the human family. Human dignity is not subjective, and pain, suffering, age, or weakness do not deprive the human being of their dignity, confirmed by the report of Mrs. Edeltraud Gatterer,[8] which preceded PACE 1418 (1999).

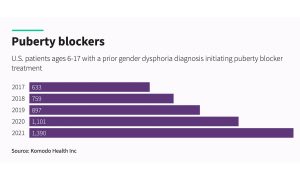

Also, the countries where euthanasia has been legalized over the last 20 years show that legislation and the protection measures are inadequate and violations frequent. While legalization begins with cases of extreme suffering, the scope of the law is rapidly expanding to situations and reasons which up until recently were not an unusual part of life, and in recent years depression, autism, struggles with sexual identity, and apprehension for a loved one were found to be sufficient reason for euthanasia. Thus, with the exception to the rule, the law creates a norm. The law that permits euthanasia is unfair because it sends a message that someone’s life is not worth living, which imposes a number of questions: who can make such a decision, according to which criteria, for which person, etc. Such a law introduces double criteria and discriminates against people with disabilities based on their disability and physical dependence in everyday needs. Disability and physical dependence on which physicians evaluate conditions for euthanasia can be seen as a deprivation of what people without disabilities often call “autonomy” and “dignity” whereby persons with disabilities can feel like a “burden” to the society. Negative consequences of such unjustified “burden” are also visible in relation to physicians who treat patients with disabilities, who want to live, in a completely different way from treating patients without disabilities but with suicidal tendencies. Abuses of laws and legal measures have been reported in various countries in many different ways, from failing to implement psychological and psychiatric assistance to disrespecting patients’ rights, organ exploitation, non-collecting information from the state supervision, failing physician guidelines and more, as can be seen in examples of Switzerland, Belgium, and Netherlands. Legalization of euthanasia in practice is a slippery slope: no matter how strict the law is, it fails to protect vulnerable groups in society.

The case of Pretty v. United Kingdom opened a debate between Articles 2 and 8 of the Convention, that has been widespread through many recent cases in many European countries, but in Croatia, this issue has not caused yet any major social, scientific or legal debate. However, one of the positive public changes was visible on the round table “Euthanasia – Dignified Death (?)” organized by World Youth Alliance Croatia. In the Republic of Croatia, euthanasia, assisted suicide, and other similar forms of intentional killing are not permitted by law and are governed by articles of the current Criminal Code, such as murder (Article 110), severe murder (Article 111), killing on demand (Article 112), assisting in suicide (Article 114), malpractice (Article 181).

discussed by many international and national regulations, and found in Articles 2 and 14 of the Convention:

“Article 2 protects everybody’s right to life. It is one of the most important articles in the European Convention on Human Rights since without the right to life it is impossible to enjoy the other rights granted by the Convention.

[…]

“(Article 14) The prohibition of discrimination is a key part of the protection of human rights. It is closely linked to the principle of equality which holds that all people are born and remain free and equal in dignity and rights.”[9]

Since human life is a fundamental good, its value is not instrumental, but is independent of conditions of the individual and is an intrinsic good in itself. The fundamental good by definition has a purpose in itself, it is chosen for the sake of itself and not for something else, and that good is realized in itself. The existence of a fundamental good in practical human experience is recognizable in different ways and situations. Everyday examples include encounters with family and friends, nature or art, or with older and wiser society members who cannot offer us any sort of material gain but nonetheless have intrinsic value. Then we realize that we know how to respect persons and things for what they are, and not for what they can do for us.

Human life is more valuable than its instrumental meaning or individual merit in society: it is the highest value and one in which every human being is equal. Because of belonging to human race, all people should be equally respected,[10]as confirmed by the judgment of the Regina v. Dudley and Stephens.[11] In the Regina v. Dudley and Stephens two shipwrecked men faced with inevitable starvation ate their cabin boy and argued that the killing was “necessary” and that the life of the cabin boy could be treated as violable because of its instrumental value in keeping them alive. The Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court rejected idea that the life of the cabin boy could be treated as violable and did so because it saw that all human lives as worthy of equal dignity and respect. If we reject the notion that all human life is equally and innately valuable and argue instead that it bears only instrumental value, the court asked, “By what measure is the comparative value of lives to be measured? Is it to be strength, or intellect, or what?” If life bears only instrumental value and may be extinguished whenever “necessary” for other ends and purposes, the court reasoned, “It is plain that the principle leaves to him who is to profit by it to determine the necessity which will justify him in deliberately taking another’s life to save his own. In this case, the weakest, the youngest, the most unresisting, was chosen.”

Respecting life as a fundamental good means making decisions in accordance with fundamental good because our decisions demonstrate what we care for and desire. Unlike unintended side effects, deliberately hurting someone represents an explicit denial that the objects of our actions possess innate value. On the other hand, based on the principle of double-effect, a patient’s death may be caused unintentionally if it is a result of a high dose of pain medication whose primary purpose is to alleviate patient’s suffering. Such side effects can lead to death, but it is important to emphasize that deliberate decision is to care for the patient rather than to kill him. We need to relate to the basic good with sincere intentions, plans and active commitment, since we are formed according to intentions and activities. Our plans and intentions tell us what we aspire to and what we will achieve. Positive examples of such deliberate decisions are many physicians, medical staff, family and friends who have years of their life dedicated to the care of patients with severe and exhausting illnesses, because they are human beings, not because of something the patients can do for them. That does not suggest that every person will dedicate their life to care for patients,

Life as the fundamental good should be experienced; simply talking about it does not need to mean much, because a book or a text cannot provide an experience of something being good or of what it means to be good. Understanding and talking about life as a fundamental good achieves its realization only through practice where it becomes clear that this is not a mere game of words.

PART 4: Conclusion

The end of life is of great significance for every person and requires true compassion and solidarity that inspire concrete actions toward the sick and dying. Palliative care approaches the end of life with respect for human dignity because it is directed towards each individual in a holistic manner, helping to their physical, mental and spiritual needs. Can someone tell a sick and dying person that their life is not worth living, that their life makes no sense, that in their life there is no room for setting new daily goals? The end of life is still a part of life which has its deep meaning and how we live it is important, not only for the reasons discussed above, but also to affirm the attitudes and goals we want to achieve, in which human dignity is respected. There is always a way, and it is important to offer a patient to live the best that they can in their final months, taking into account all aspects of his situation, believing that he will find support and meaning in them.

Respect for every human life as a fundamental good is the foundation of a society of justice and solidarity. Illness, suffering or any other form of external influence on life does not destroy human dignity. Aging and dying can bring their own difficult moments, but the attitude we take at each moment depends on us. Such an attitude for everyone should encourage us to live life in its fullness and motivates us to set new goals every day according to our possibilities. The beauty of life can be found everywhere, and examples from everyday life help us understand better with our own experience that life it is truly worth living. Research show us that the majority of people at the end of life find it important to feel comfortable, to spend the last moments in the circle of their family and friends, not feel like the burden to others, and that their religious and spiritual beliefs are respected.

By respecting the will and rights of patients, we have a mission in our own life to make the world a warmer, more humane and more secure place, in which we are guided by a system of values which is in accordance with human dignity and life as a fundamental good.

To respect human dignity, as well as life in its fullness until natural death, should be the greatest challenge for all healthcare professionals. Physicians and medical staff, with their knowledge and experience, but above all with their have the task of bringing the peace to those who leave and those who continue to live. It is an extraordinary task full of responsibility, beauty and new challenges: to know oneself by going beyond oneself and investing in the benefit of others.

Philosopher Ferdinand Ebner summed it up: “A neighbor and a friend: we all look for the one with whom we can be human. We must not live next to the man, but with him. And it is even better when we live each other.”

[1] Pretty v. the United Kingdom, Ap. 2346/02, judgment of 29 April 2002.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The death penalty currently regulated by Protocols 6 and 13 of the Convention expects further regulation: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/DeathPenalty/Pages/DPIndex.aspx, access: May 21, 2017

[4] Pretty v. United Kingdom §65; McCann and Others v. United Kingdom, judgment 27 September 1995, §147; Streletz, Kessler and Krenz v. Germany, Ap. 34044/96, 35532/97 and 44801/98, §§ 92-94

[5] See the preparatory work of the Consultative Assembly of 1949: “the Committee of Ministers has entrusted us to establish a list of rights including the rights, a human being, should naturally enjoy,” Travaux Preparatoire, Vol. II, 89.

[8] Edeltraud Gatterer, Doc. 8421, Protection of the human rights and dignity of the terminally ill and the dying, Report from Social, Health and Family Affairs Committee, “3. Dignity is bestowed equally upon all human beings, regardless of age, race, sex, particularities or abilities, of conditions or situations, which secures the equality and universality of human rights. Dignity is a consequence of being human. Thus a condition of being can by no means afford a human being its dignity nor can it ever deprive him or her of it. 4. Dignity is inherent in the existence of a human being. If human beings possessed it due to particularities, abilities or conditions, dignity would neither be equally nor universally bestowed upon all human beings. Thus a human being possesses dignity throughout the course of life. Pain, suffering or weakness do not deprive a human being of his or her dignity.”

[9] Council of Europe, Teaching Materials, Rights and Freedoms in Practice, pp. 6, 10, available at http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Pub_coe_Teaching_resources_ENG.pdf.

[10] Neil M. Gorsuch, The future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540, (2009), 159

[/tab]

[tab title=”Hrvatski”]

I pravni aspekt rasprave o kraju života obilježen je suvremenim liječničkim zahvatima u život bolesnih i umirućih, pravom na život dotičnih, njihovim temeljnim slobodama, pravom na poštivanje privatnog i obiteljskog života te ostalim pravima u skladu s nacionalnim i međunarodnopravnim uređenjem, primjerice Opća deklaracija o ljudskim pravima (dalje: Deklaracija), Europska konvencija za zaštitu ljudskih prava i temeljnih sloboda (dalje: Konvencija), Europska socijalna povelja i drugi.

Temelj društvene i političke posvećenosti ljudskoj jednakosti nalazi se u čvrstom uvjerenju kako svaka ljudska osoba ima dostojanstvo na temelju kojeg joj pripadaju prava i poštovanje zato što je ljudska osoba, neovisno o rasi, spolu, izgledu, vjeri ili drugim karakteristikama. Međunarodnopravni okvir štiti pravo na život svake osobe, koje je prvo među nabrojenim pravima Konvencije, te od ostalih država zahtijeva zaštitu života najranjivijih i najugroženijih. Važno je napomenuti kako međunarodnopravni propisi niti prepoznaju takozvano „pravo na smrt“ niti je ono dio međunarodnopravnih smjernica. Osim u zaštiti najranjivijih pojedinaca, država ima interes zaštiti etički integritet medicinske profesije kako bi osigurala povjerenje građana u medicinsku struku.

Sustavna zaštita prava pacijenata na europskom tlu započela je dokumentom „Prava bolesnika i umirućih“ koji je donijela Savjetodavna skupština Vijeća Europe 1976. godine, a dopunjen je 1979. godine od strane Bolničkog povjerenstva Europske zajednice dokumentom „Povelja o bolesniku, korisniku bolnice.“ U cilju sprečavanja situacija u kojima se bolesniku ne pridaje dovoljno pažnje i ne postupa u skladu s njegovim dostojanstvom, navedeni dokumenti razrađeni su na temelju članaka Deklaracije i Europske socijalne povelje. Suvremene pravne rasprave na ovu temu najčešće uključuju Konvenciju od članka 2., koji od države zahtijeva ne samo uzdržavanje od nanošenja smrti nego i zaštitu života, do članka 8. koji jamči pravo na poštivanje privatnog života.

Dodatan doprinos Vijeća Europe temi vidljiv je kroz nekoliko dokumenata koji su potvrdili konsenzus europskih zemalja koje se protive praksi eutanazije i potpomognutog samoubojstva. Izdvajamo dvije Preporuke i jednu Rezoluciju usvojene od strane Parlamentarne skupštine Vijeća Europe:

– Preporuka 779 (1976) „… liječnik mora poduzeti sve napore kako bi ublažio patnju i nema pravo, čak ni u slučajevima koji mu se čine očajnim, namjerno ubrzati prirodni tijek smrti“ (§7).

– Preporuka 1418 (1999) potvrđuje da pravo na život bolesnih i umirućih mora biti jamčeno i u slučajevima kada pacijent izriče želju za smrću.

– Rezolucija 1859 (2012): „Eutanazija, u smislu namjernog ubijanja aktivnim djelovanjem ili propustom ovisnog ljudskog bića za njegovu ili njezinu navodnu korist, mora uvijek biti zabranjena.“

Mehanizam osiguranja provođenja Konvencije jest Europski sud za ljudska prava (dalje: Sud) kojemu se stranke sukladno članku 34. Konvencije mogu obratiti u slučajevima povrede temeljnih ljudskih prava i sloboda zajamčenih Konvencijom. Presuda Suda koja je inicirala pravni aspekt rasprave o kraju ljudskog života jest u slučaju Pretty protiv Ujedinjenog kraljevstva iz 2002. godine, kojom je odbijena žalba neizlječivo bolesne britanske državljanke Diane Pretty i uskraćeno “pravo na smrt” eutanazijom.[1] Navedeni slučaj Suda važan je zbog sljedeća dva elementa:

1) „Članak 2. ne može se, ne narušavajući jezik, tumačiti na način da se priznaje postojanje dijametralno suprotnog prava, prava na smrt; niti se može uspostaviti pravo na samoodređenje u smislu prava pojedinca da izabere smrt umjesto život“ (§ 39).

[…]

„Pravo na smrt, bilo da je riječ o trećoj osobi ili uz pomoć tijela javne vlasti, ne može biti izvedeno iz članka 2. Konvencije“ (§ 40).

2) „Države ugovornice uživaju diskreciju (engl. Margin of appreciation) o tome da li i u kojoj mjeri razlike u inače sličnim situacijama opravdaju različit tretman“ (§ 87).[2]

Ovom je presudom, prvo, jasno odijeljena razlika između prava i sloboda te naglašeno da iz prava na život ne možemo doći do takozvanog „prava na smrt“. Dok slobode imaju pozitivan (pravo na djelovanje) i negativan aspekt (pravo na nedjelovanje) u slučaju zaštite života, Sud izrijekom navodi kako pravo na život nema dijametralno suprotno pravo. Drugo, Sud je o ovoj temi utvrdio kako države ugovornice prema konceptu „margin of appreciation“ imaju određenu diskreciju u odlukama gdje treba uravnotežiti prava pojedinca i interes društva.

Članak 2. Konvencije navodi kako “Nitko ne smije biti namjerno lišen života…”, kao i iznimke ovog prava koje Konvencija propisuje radi zaštite općeg interesa ili višeg cilja, no one ne uključuju ni zahtjev ni suglasnost zainteresiranih stranaka za eutanazijom ili potpomognutim samoubojstvom. Život i pravo na život temelji su iz kojih proizlaze sva druga prava i ljudske vlastitosti s kojima su eutanazija i potpomognuto samoubojstvo u očitom proturječju.[3] Slučajem Pretty protiv Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva potvrđeno je kako pravo na život „predstavlja neotuđivo svojstvo ljudske osobe i vrhovna je vrijednost u ljestvici ljudskih prava“[4] koje štiti „svaku osobu.“[5]

Koncept ljudskih prava podrazumijeva zaštitu ljudske osobe od toga da ona postane objektom borbe za vlast i interese države, te naglašava kako čovjeka u njegovom dostojanstvu uvijek trebamo promatrati kao cilj, a nikad kao sredstvo. Intrizično dostojanstvo osobe ne ovisi o nekoj okolnosti te ga nijedno društvo ili država ne može dati ili dokinuti jer u dostojanstvu pojedinac nadilazi državu. Ljudsko dostojanstvo koje je temelj i prethodi Deklaraciji, inspiracija je Konvenciji koja je utemeljena na prepoznavanju inherentnog dostojanstva svih članova ljudske obitelji. Ljudsko dostojanstvo nije subjektivno, a bol, patnja, dob ili slabost ne lišavaju ljudsko biće njegovog dostojanstva, potvrđeno je i u izvješću gđe Edeltraud Gatterer,[6] koje je prethodilo Preporuci 1418 (1999) Parlamentarne skupštine Vijeća Europe.

Također, države u kojima je eutanazija legalizirana u zadnjih više od 15 godina pokazuju kako su zakonodavstvo i zaštitne mjere nesigurni, nepravedni te su česti slučajevi kršenja zakona. Dok legalizacija počinje sa slučajevima ekstremne patnje, opseg zakona ubrzo se širi do situacija i razloga koje donedavno nisu bile neuobičajen dio života pa su proteklih godina depresija, autizam, problematičan spolni identitet i žalovanje za voljenom osobom bile dovoljan razlog za eutanaziju. Tako, iznimkama u zakonu, zakon stvara pravilo. Zakon koji dopušta eutanaziju nepravedan je jer šalje poruku da nečiji život nije vrijedan življenja što postavlja niz pitanja: tko može donijeti takvu odluku, prema kojim kriterijima, za koju osobu itd. Takav zakon uvodi dvostruke kriterije i diskriminira osobe s poteškoćama na temelju njihovih nesposobnosti, invaliditeta i fizičke ovisnosti prilikom svakodnevnih potreba. Invaliditet i fizička ovisnost prema kojima liječnici procjenjuju uvjete za eutanaziju mogu se promatrati kao lišavanje onoga što osobe bez poteškoća često zovu „autonomija“ i „dostojanstvo“ zbog čega se osobe s invaliditetom mogu osjećati kao „teret“ okolini i društvu. Negativne posljedice takva nepravedna „tereta“ vidljive su i u odnosu na liječnike koji osobe s poteškoćama koje bez obzira na sve žele živjeti liječe potpuno drugačije od osoba bez poteškoća sklonih samoubojstvu. Kršenje zakona i zakonskih mjera zabilježeno je u različitim državama na mnogo različitih načina, od neprovođenja psihološke i psihijatrijske pomoći, do nepoštivanja prava pacijenata, eksploatacije organa, neprikupljanja informacija od strane državnog nadzora, nepraćenja smjernica od strane liječnika i slično, što je vidljivo na primjerima Švicarske, Belgije, Oregona te Nizozemske. Legalizacija eutanazije u praksi predstavlja sklizak teren – bez obzira na to koliko zakon bio strog, ne uspijeva zaštititi ranjivu skupinu društva.

Slučaj Pretty protiv Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva otvorio je raspravu između članka 2. i 8. Konvencije koji se nizom nedavnih slučajeva proširio mnogim europskim zemljama, ali u Hrvatskoj tema još nije izazvala veću društvenu, znanstvenu niti pravnu raspravu. Ipak, jedan od pozitivnih pomaka javnog karaktera teme bio je vidljiv na okruglom stolu „Eutanazija – dostojanstvena smrt (?)“ u organizaciji Svjetskog saveza mladih Hrvatska. U Republici Hrvatskoj eutanazija, potpomognuto samoubojstvo i drugi slični oblici usmrćenja na zahtjev nisu zakonom dopušteni, a regulirani su pojedinim člancima trenutnog Kaznenog zakona, kao npr: ubojstvo (čl. 110), teško ubojstvo (čl. 111), usmrćenje na zahtjev (čl. 112), sudjelovanje u samoubojstvu (čl. 114), nesavjesno liječenje (čl. 181).

Kvalitetnoj javnoj raspravi doprinosi i argument da je život temeljno dobro, o kojem pišu mnogi međunarodnopravni i nacionalni propisi, a iščitavamo ga iz članaka 2. i 14. Konvencije:

„Članak 2. štiti pravo svakog na život. To je jedan od najvažnijih članaka Europske konvencije o ljudskim pravima jer je bez prava na život nemoguće uživati ostala prava zajamčena Konvencijom.

[…]

(Članak 14.) Zabrana diskriminacije ključan je dio zaštite ljudskih prava. Usko je vezana s načelom jednakosti koja drži da su svi ljudi rođeni i ostaju slobodni i jednaki u dostojanstvu i pravima.“ [7]

Budući da je ljudski život temeljno dobro, njegova vrijednost nije instrumentalna, neovisna je o uvjetima i stanju pojedinca te je intrizično dobro samo po sebi. Temeljno dobro prema definiciji, ima svrhu u samom sebi, ono se odabire radi sebe samoga, a ne radi nečeg drugog, i to dobro ostvaruje se samo po sebi. Postojanje temeljnog dobra u praktičnom ljudskom iskustvu prepoznatljivo je u različitim situacijama i načinima. Primjeri za to su susreti s obitelji i prijateljima, s dojmljivim prizorima prirode ili umjetnosti, sa starijim i mudrijim članom društva u kojima ne vrednujemo samo instrumentalnu i potencijalnu korist koju oni nose u sebi, nego jednostavno poštujemo unutarnju vrijednost koju ti dijelovi stvarnosti posjeduju. Tada shvaćamo da osobe i stvari znamo poštivati zbog onoga što one jesu, a ne zbog onoga što za nas mogu učiniti.

Ljudski život vrijedniji je od njegovog instrumentalnog značenja ili zasluge pojedinca u društvu – on je najveća vrijednost po kojoj je svako ljudsko biće jednako. Zbog pripadnosti ljudskoj vrsti, sve ljude treba jednako poštovati,[8] što je potvrdila i presuda Regina protiv Dudleya i Stephensa.[9] U slučaju Regina protiv Dudleya i Stephensa dvije osobe nakon preživljenog brodoloma suočeni s neizbježnim gladovanjem pojeli su mladića koji je posluživao na brodu tvrdeći kako je ubijanje bilo “neophodno” te je život mladića mogao biti oduzet zbog instrumentalne vrijednosti održavanja njihova dva života. Kraljičin odjel Visokog suda odbio je ideju kako je život mladića mogao biti narušen zbog instrumentalne vrijednosti i postupio je tako vidjevši kako je svaki ljudski život jednako vrijedan u dostojanstvu i poštovanju. Ako odbacimo ideju da je svaki ljudski život jednako i urođeno vrijedan, a umjesto toga tvrdimo kako on nosi samo instrumentalnu vrijednost, Kraljičin odjel Visokog suda je pitao: “Kojom mjerom možemo usporediti relativnu vrijednost života? Je li to snaga, intelekt ili što?” Ako život nosi samo instrumentalnu vrijednost i može biti oduzet kad god je to “neophodno” za druge ciljeve i svrhe Kraljičin odjel Visokog suda je zaključio: “Jasno je kako onaj koji iz situacije izlači probitak za vlastitu odluku utvrđuje nužnost putem koje traži opravdanje za namjerno oduzimanje drugog života da bi spasio vlastiti. U ovom slučaju, izabran je najslabiji, najmlađi, najneodrživiji.”

Poštivati život kao temeljno dobro znači odabirati naše namjerne radnje u skladu s temeljnim dobrom, jer nam naše namjerne radnje govore do čega nam je stalo i što želimo. Za razliku od nenamjernih pojava, namjerno povrijediti nekoga poriče da je predmetu našeg djelovanja svojstvena unutrašnja vrijednost. S druge strane, po načelu dvostrukog učinka, smrt pacijenta može biti nenamjerna pojava ako je posljedica visoke doze lijeka protiv bolova kojima je prvotna svrha ublažiti patnju pacijentu. Takva nuspojava može dovesti do smrti, ali važno je naglasiti kako je prvotna namjera brinuti se za pacijenta, a ne ubiti ga. Prema temeljnom ili urođenom dobru treba se odnositi s iskrenom namjerom, planovima i aktivnim zalaganjem jer prema namjeri i aktivnosti postajemo ono što želimo biti. Naši planovi i namjere govore do čega držimo, kamo težimo i što ćemo postići. Pozitivni primjeri takvog odabira mnogi su liječnici, medicinsko osoblje, obitelj i prijatelji koji su godine svojih života posvetili brizi o bolesnicima s teškim iscrpljujućim bolestima zbog toga što su bolesnici ljudske osobe, a ne zbog instrumentalnog ostvarenja skrivenih ciljeva. Navedenim se ne tvrdi da će se svaka osoba posvetititi brizi o pacijentima, ali činjenica kako su neki ljudi izabrali ovaj način života, dokaz je kako život možemo prepoznati kao temeljno dobro i življeti u skladu s tom spoznajom.

Život kao temeljno dobro treba doživjeti, o njemu samo govoriti ne mora značiti puno, jer ne može se iz knjige ili teksta iskusiti kako je nešto dobro ili kako biti dobar. Razumijevanje i govor o životu kao temeljnom dobru dobiva svoje oživotvorenje tek u praksi gdje postaje jasno kako se ne radi o pukoj igri riječi.

4. DIO: ZAKLJUČAK

Kraj života tema je od velikog značaja za svaku osobu i zahtijeva istinsku suosjećanost i solidarnost koje potiču na konkretno djelovanje prema bolesnima i umirućima. Dostojanstven pristup kraju života predstavlja palijativna skrb jer je usmjerena prema svakom pojedincu na cjelovit način pomažući prema njegovim tjelesnim, psihičkim i duhovnim potrebama. Može li tko bolesnom i umirućem reći da njegov život nije vrijedan življenja, da njegov život nema smisla, da u njegovom životu nema prostora za postavljanje novih svakodnevnih ciljeva? Kraj života i dalje je dio života, koji ima svoj duboki smisao i važno je kako ćemo ga proživjeti, između navedenog, i zbog afirmacije stavova i ciljeva koje želimo postići. Uvijek postoji način i važno je ponuditi ga pacijentu kako bi živio dostojanstven i kvalitetan život istovremeno vodeći računa o svim aspektima njegove situacije, vjerujući da će on u njima pronaći potporu i smisao.

Poštivanje svakog ljudskog života kao temeljnog dobra temelj je pravednog i solidarnog društva, a bolest, patnja ili bilo koji drugi oblik vanjskih utjecaja na život ne uništava ljudsko dostojanstvo.

Starenje i umiranje mogu nositi svoje teške trenutke, ali stav koji zauzimamo prema svakom trenutku ovisi o nama. Takav stav za svakoga treba biti odraz smisla koji nas potiče živjeti punim životom i motivira na svakodnevno postavljanje novih ciljeva u skladu s mogućnostima. Ljepotu življenja možemo pronaći svugdje, a primjeri iz svakodnevnog života pomažu nam da kroz vlastito iskustvo razumijemo dublje kako uistinu vrijedi živjeti. Iz istraživanja znamo kako je većini osoba na kraju života važno osjećati se udobno, posljednje trenutke provesti u krugu obitelji i prijatelja, ne osjećati se kao teret drugima, te da se njihova vjerska i duhovna uvjerenja poštuju.

Poštujući volju i prava pacijenata, zadatak nam je u vlastitom životu vlastitom osobom svijet činiti svjetlijim, toplijim i ljudskijim u čemu nas vodi sustav vrijednosti uređen prema ljudskom dostojanstvu i životu kao temeljnom dobru.

Sačuvati ljudsko dostojanstvo, život u svoj njegovoj punini do prirodne smrti, treba biti najveći izazov za sve profesionalce u palijativnoj skrbi. Na liječnicima i medicinskom osoblju je da znanjem i iskustvom, ali prije svega etičkim pristupom i stalnom izgradnjom vlastite osobnosti, budu donositelji mira onima koji odlaze kao i onima koji ostaju. Iznimna je to zadaća puna odgovornosti, ljepote i zanosa – zadaća biti čovjek koji samoga sebe upoznaje nadilazeći se i ulažući u korist drugoga!

Filozof Ferdinad Ebner ovu je poruku sažeo: „Susjeda i bližnjega – svi mi tražimo onoga s kim možemo biti čovjek. Ne smijemo živjeti kraj čovjeka, nego s njim. A još bolje je kad živimo jedni druge.“

[1] Pretty protiv Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva, br. 2346/02, presuda od 29. travnja 2002. godine

[2] Ibid.

[3] Smrtna kazna trenutno regulirana protokolima 6. i 13. Konvencije očekuje daljne regulacije. Vidi: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/DeathPenalty/Pages/DPIndex.aspx, pristup: 21. svibnja 2017.

[4] Pretty protiv Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva §65; McCann i ostali protiv Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva, presuda 27. rujna 1995. godine, §147; Streletz, Kessler i Krenz protiv Njemačke, br. 34044/96, 35532/97, 44801/98, §§ 92-94.

[5] Vidi pripremne radove Savjetodavne skupštine iz 1949. godine: “the Committee of Ministers has entrusted us to establish a list of rights including the rights, a human being, should naturally enjoy” Preparatory Works, Vol. II, p. 89.

[6] Edeltraud Gatterer, Doc. 8421, Protection of the human rights and dignity of the terminally ill and the dying, Report from Social, Health and Family Affairs Committee, “3. Dignity is bestowed equally upon all

human beings, regardless of age, race, sex, particularities or abilities, of conditions or situations, which secures the equality and universality of human rights. Dignity is a consequence of being human. Thus a condition of being can by no means afford a human being its dignity nor can it ever deprive him or her of it. 4. Dignity is inherent in the existence of a human being. If human beings possessed it due to particularities, abilities or conditions, dignity would neither be equally nor universally bestowed upon all human beings. Thus a human being possesses dignity throughout the course of life. Pain, suffering or weakness do not deprive a human being of his or her dignity.”

[7] Council of Europe, Teaching Materials, Rights and Freedoms in Practice, pp. 6, 10, available at http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Pub_coe_Teaching_resources_ENG.pdf.

[8] Neil M. Gorsuch, The future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540, (2009), 159

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Written by Luka Poslon, head of the Bioethics Team of WYA Croatia