Man´s search for meaning is one of those unforgettable books that can provoke a change in your way of looking at life and the people around you.

The book has two clearly differentiated parts. On the one hand, the first half of Man’s Search for Meaning describes life in Nazi concentration camp in light of the author’s discovery of meaning as a key survival factor. On the other hand, in the second part of the book, Frankl explains Logotherapy, his method of “curing the soul by leading it to find meaning in life.”

As Frankl describes it, this meaning is found by realizing the intrinsic dignity that he and others possessed simply as human beings.

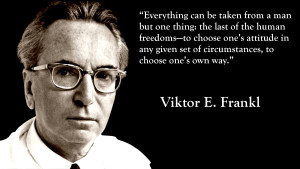

Even having been lowered into the pits of humanity, Frankl emerged an optimist. His reasoning was that even in the most terrible circumstances, a person still has the freedom to choose how they handle their circumstances and create meaning out of them. As Frankl describes it, this meaning is found by realizing the intrinsic dignity that he and others possessed simply as human beings.

In another words, Frankl argues that we cannot avoid suffering, but we can choose how to cope with it, find meaning in it, and move forward with renewed purpose. By choosing to exercise his ability to control his reactions and the way he treated others, Frankl discovered the ultimate meaning of freedom. This kind of freedom enabled him to defy his oppressors because no matter what they said or did they could not make him believe that any human life—including his own—was worthless. Along the book, he exposes how the pursuit of this resistance gave him meaning and allowed him and so many others to endure one of the most difficult burdens in human history: a Nazi concentration camp. As Gordon Allport notes in his Preface to the third edition, this is what the ancient Stoics called the ‘last freedom’. This ultimate human freedom is the freedom to control our attitude toward the situations we inherit.

In the midst of the horror, Frankl tried to understand “the apparent paradox that some prisoners of a less hardy make-up often seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature.” He endured the torture of the SS guards, the injustice of being beaten and broken, and the pain of seeing those around him “treated like nonentities”. Eventually he found what carried some through to the end: meaning. He knew that the SS guards were wrong. Human dignity, being inherent, cannot be taken away, and despite his suffering and the constant messages that told him he was worthless Frankl clung to the belief that his life had meaning.

Human dignity, being inherent, cannot be taken away, and despite his suffering and the constant messages that told him he was worthless Frankl clung to the belief that his life had meaning.

It was meaning, or the seeking for meaning in one’s life, that made the difference. Not a general “meaning of life” feeling, but particular purposes that “differ from man to man, and from moment to moment.” For Frankl during his time in the camp, the desire to see his wife again and his hope of publishing a book on his psychiatric theories gave him a reason to hope that helped bring him through his nearly three years of captivity

Another remarkable aspect of the book is how the author is able to write about his experiences entirely without bitterness or vengefulness. Additionally, he does not lose his faith in humanity and is able to discover the goodness even among his enemies. Frankl tells the story of a camp commander, a Nazi, who used his own money to buy medicines for the prisoners from a nearby town. Upon liberation by Allied forces, the prisoners protected this “enemy” from harsh treatment by their rescuers.

This kindness for a tender heart, even in an enemy’s garb, made Frank`s realized that: “There are two races of men in this world, but only these two—the ‘race’ of the decent man and the ‘race’ of the indecent man. Both can be find everywhere; they penetrate into all groups of society. No group consists entirely of decent or indecent people. In this sense, no group is of ‘pure race.’

María Estraviz did her first WYA internship with WYA Europe, and is currently part of the International Internship Program for the WYA Headquarters in New York City.

Find out more about what Viktor Frankl has to say by starting your WYA Track A Training today.

Like what you’re reading? Be sure to follow us on Facebook, where you can catch all our WYA Blog content including film reviews such as this one.

For even more information on what we’re watching, check out our Recommended Film List or join a WYA discussion group.

Header image from http://probarney.com.